A Brief Town History

Updated 14 December 2025

PRE-NORMAN TIMES

In 1869 and 1881 workers digging on the south slopes of Broad Hill came across 2 granite lined chambers 12m apart. The second one was better preserved with yellow plaster and red and black stripes painted on the wall with here and there hints of a red on white pattern too. Shards of bone and oyster shells on the floor of this second chamber, along with pieces of Swithland slate that might have at one point formed a roof. The next earliest finds in the area come from a team of workers excavating on the same hill in 1892 who came across an historic well containing Romano-British ceramics, animal bones and a metal plated bucket. This has been dated to the 3rd or 4th century CE and indicates a local population in this period.

As for the next period of English history, the arrival of the Angles in the area in about the 5th century CE, there has been very little or no history discovered about our part of the kingdom of Mercia, (although anything on Castle Hill would likely have been destroyed by the later Norman building works).

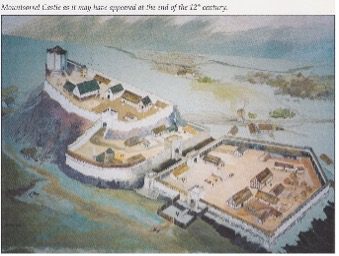

THE CASTLE, THE REVOLT OF 1173 AND THE FIRST BARONS’ WAR

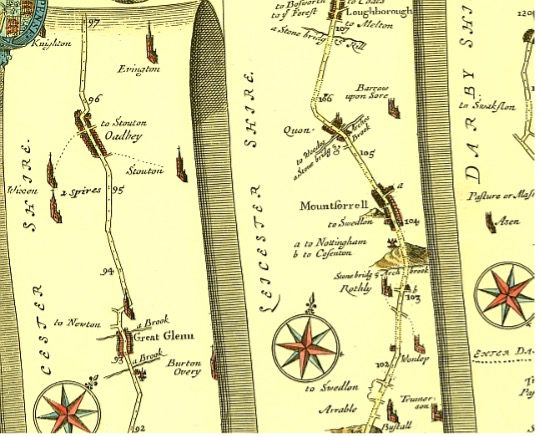

By far the biggest impact on the area by the Normans after their invasion of 1066 was the construction of castle on the rocky hill overlooking the valley below. There is no mention of the town or manor of Mountsorrel in The Conqueror’s Doomsday Book of 1086, but the manors of Barrow and Rothely DID exist and the castle pretty much sat on top of the border with the division itself likely up the line of what is now Watling Street. Barrow was under the control of the Earl of Chester, whilst Rothely to the south fell was part the Earl of Leicester’s territory. These two Earl’s had an ongoing private war and the castle’s ownership would form a large part of that.

The County antiquarian John Nichols writing in c1800 says the castle was probably constructed in about 1080 by Hugh d’Ávranches, Earl of Chester (also called Hugh Lupus and Hugh the fat) modern historians’ question this and think it may have been in the control of the Earls of Leicester from the outset. It was certainly in Leicester control at the time of the lengthy private war between the Earls and caused by Leicester taking over tracts of Chester lands. The peace treaty and follow-on non-aggression pact negotiated by the Bishop of Lincoln leaves the castle in Leicester’s hands but gives Chester access to it and the Borough of Mountsorrel.

In 1173 the 3rd Earl of Leicester sided with a rebellion again King Henry II in the name of his eldest legitimate son (also called Henry). After a siege in 1174 the castle was taken over by the King and even after the Earl of Leicester repented and gained most of his lands back, the King still kept hold of Mountsorrel Castle, much to the annoyance of the Earl’s family.

The castle remained in the King’s possession until being granted to Saer de Quincy by the then current king, King John. Unfortunately for the King, at the start of the First Baron’s War, de Quincy sided with the rebel barons who were trying to place Prince Louis of France on the English throne in King John’s stead and the castle became a rebel stronghold (again). Raiding through the local area to support the garrison, the castle gained a reputation of being “a nest of the Devil and den of thieves and robbers”- very flattering!

King John’s death in 1216 didn’t stop the rebellion, and his 9 year old son was crowned Henry III whilst guided and guarded William Marshall, 1stEarl of Pembroke who was effectively the Regent. Marshall was supported by Ranulf de Blondeville, 6th Earl of Chester, who was despatched with several other leading loyal barons to recover the castle.

During the ensuing siege in April-May 1217 Chester’s scouts reported the imminent arrival of a large French relief force and he pulled his forces back to Nottingham. The report was in error as it was only half the French army who arrived at Mountsorrel, they secured the castle for the rebels and then pillaged their way across the Vale of Belvoir and on to Lincoln to join the rebel siege of the castle there.

William Marshal now joined with Chester circled round to the west of Lincoln, entered the castle and then trapped the rebel baronial and French forces those forces inside the city walls below the castle. There Marshall and Chester personally led a bloody assault against them during which the Marshall of France, Comte Thomas de Perche was killed and the rebel forces crushed in the battle now known now as “The Lincoln Fair”. The defeat led eventually to Prince Louis giving up his (tenuous) claim to the English throne and departing for France; later that year Ranulf de Blondeville was also given the newly created title 1st Earl of Lincoln – to the victor go the spoils

Having been held against the crown twice in a little over 40 years, the King decided that the castle was a far too valuable and strategic an asset to let fall into the wrong hands again. In the aftermath to the battle he gave control to the Earl of Chester who rode south and ordered it razed to the ground.

During the years of the castle’s presence on the hilltop, a small village would have grown up around it to service the needs of its residents and garrison. Forming a rough triangle, this village would have formed around what is now Market Place to the east along the valley road, The Green to the south and Watling Street to the north of the castle itself.

THE ENGLISH CIVIL WARS / WARS OF THE THREE KINGDOMS

This section covering this time period is actually still in progress, as both ourseves and the Mountsorrel Heritage Group research it further, however many of the facts below are drawn from Capt.Lt.Palmer’s deposition in front of the Committee at Leicester given on 30 May 1644 after their defeats at both Cotes Bridge and Newark (sorry about the spoiler there!).

In March 1644 the Royalist town of Newark was under seige by a Parliament army and a relief force had been ordered by King Charles to go there break the seige. The King’s nephew, Prince Rupert of the Rhine (Ruprecht von der Pfalz, Duke of Cumberland, to give him his full name), was ordered to take a force from his base in Chester to Newark to do this. From Chester he planned to pass through his local garrisons and then Ashby-de-la-Zouch to pick up more troops before heading to Loughborough and then on towards Newark.

The problem with this plan was the Parliament garrison in Leicester which was ideally placed to intercept Prince Rupert’s advance before it got to Loughborough. To head this off, Henry Hastings dispatched a force of about 600 troops from Ashby along with a couple of cannon under the command of Sir Gervaise Lucas to Leicester to keep them otherwise occupied until it was too late to intercept the main body.

After they had successfully completed this mission they withdrew northwards along the western back of the River Soar to Mountsorrel on way to leicester to meet up with Prince Rupert. Whilst in town they decided to billet and rest in the local inns and taverns.

On March 15th, a Parliamentary detachment from Newark commanded by Sir Edward Hartropp (Hartop/Hartrup are known alternate spellings) was shadowing this force as it headed north but along the opposite eastern bank of the river with a force of up to 2000 soldiers, (mostly cavalry and dragoons drawn from the brigades of Manchester, Derbyshire, Lincolnshire and Nottingham). Hartropp also sent a scouting troop of approx 60-70 light cavalry (Notts Horse) to follow the Royalists more closely up the western bank; this was under the command of Capt.Lt.George Palmer (the in-field commander of the Notts Horse whilst their overall commander, Col.Thornhaugh, had remained behind at Newark).

This scouting troop was tasked with taking a small hill between Rothley and Mountsorrel from which to observe the local area (this hill/ridge of higher ground sits close to where Rothley Lodge once stood and is now behind the Mountview care home but sadly built over by the A6 bypass). On approaching the hill, the cavalry came across a group of Royalist soldiers trying to make off with a farmer’s plough horses and attacked them, successfully driving most of them off and capturing 3 others. The escaping soldiers quickly warned the rest of their comrades of the unexpected close proximity of the enemy cavalry.

Capt.Palmer then sent word back to Edward Hartropp that he needed reinforcements in order to attack the town which was now aware of his presence; Hartropp informed him that he had moved too fast for the main body to assist and that he was not to attack but to hold position outside the town. This order was reinforced by being hand delivered by another troop commander, Capt.Innys/Ennys (spelling was a bit erratic back then). Whilst these orders were being passed around the defenders of Mountsorrel had roused themselves from the inns and taverns that they had been “relaxing” in and had formed up ready to meet the Parliament forces in the fields to the south of the town.

Ignoring the orders of Colonel Hartropp, and in agreement with Palmer, (probably sensing too much of a good opportunity to miss), Captain Innys agreed to attack the town using his own authority, he and Palmer then charged into Mountsorrel along with the rest of the cavalry scout force. This attack was a huge success and they quickly overran the defenders sweeping into the town and taking it, they quickly set about looting all the spoils of war that they could. Once again Palmer called for reinforcements whilst setting about barricading themselves in the town centre against the inevitable counter attack from the rapidly reorganising defenders.

Colonel Hartropp was furious that his orders had been disobeyed and refused to send any extra troops to aid Palmer and Innys. Upon realising that the attackers were on their own, the Royalists took their revenge and attacked hard enough to push Palmer out of the town and across the Sileby Road (formerly called York Street) bridge (the original 4-arched medieval stone and rubble one that stood where the new metal bridge near “The Waterside” pub now sits) leaving behind his newly acquired loot and prisoners. These prisoners had included a Major Jammot, a well-known senior [French] Royalist officer. The severity and speed of this counter attack isolated a section of Palmer’s troop from any possible retreat and they continued to fight to avoid being killed or captured.

On reaching the main force again, Palmer demanded a meeting with Hartropp and called for more troops to mount a rescue for those that been left behind (as well as a fresh horse). Both demands were refused! Hartropp then threatened Palmer with a Court Martial unless he stood down immediately. The rest of Hartropp’s command had been steadily getting more and more unhappy with how Palmer was being treated and the fact that part their force was seemingly being abandoned to their fate and started openly backing his call for a rescue mission. Major Thomas Sanders/Saunders from the Derbyshire Horse gave him a remount from his own company and a troop of dragoons (likely from the Earl of Manchester’s detachment) joined with Palmer’s remaining troops and jointly attacked back over the bridge again, once more against the explicit orders of Hartropp.

The counterstrike was a success and the remaining previously cut off troops were extracted to behind fresh baricades in the town centre. Hartropp once more ordered that all the cavalry and dragoons withdraw back over the bridge to their own lines immediatley despite the town now being mostly under Parliament control oncew again. This was done, but in doing so all of Palmer’s stores and provisions had to be abandoned in order to withdraw at the necessary speed.

The 2 forces, now on opposite sides of the river once more, steadily moved north 5 miles towards Loughborough (The Royalists moving overnight, and Hartropp inexplicably taking 2 days for the short move).

This set the scene for the following much larger battle at Cotes Bridge (in Loughborough) on the 17th/18th March and the following relief of the Parliamentary siege of Newark on the 21st.

Local legend has it that Slash Lane (which used to join Sileby Road a lot closer to the bridge than it does now) got it’s name from the fighting around there…..

As well as this major action there were 2 other notable local events during the English Civil Wars, in 1642 and 1660.

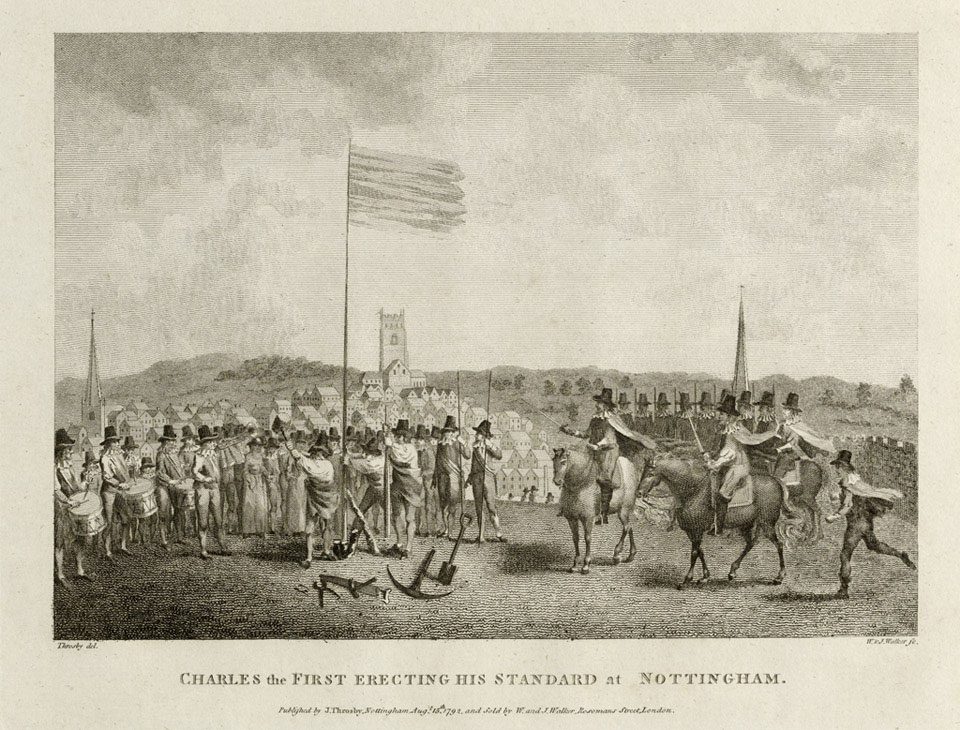

In August 1642 a group of officers on their way to support King Charles in Nottingham as he raised his banner against Parliament are said to have stayed in a house/barn at the bottom of Crown Lane (maybe that’s why it’s called Crown lane??). King Charles himself is known to have stayed in Cavendish House in Leicester on 21st August before travelling to Nottingham on the 22nd so would have travelled through the town as well.

and

In 1660, Colonel George Monk’s regiment passed through town on their 5 week march from Coldstream to London where they were instrumental in the restoration of the monarchy under King Charles II. They would in 1670 become the “Coldstream Regiment of Footguard” and are now the longest continuously serving regiment in the British Army

THE MARKET

On 14th July 1292, the Lord of the Mountsorrel Manor, Nicholas de Seagrave, was granted the right by King Edward I to hold a market every Monday and a yearly fair on the “eve and morrow of St John the Baptist and 5 days after“. The popularity of the fairs seems to have died away in the 15th century but once more became busy again with more houses being built along Main Street (Loughborough Road now) in the 1600s.This fair lasted until 1873.

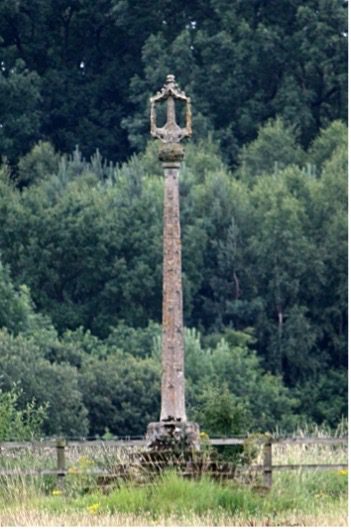

In 1793 the Lord of the Manor, Sir John Danvers, removed the ancient market stone cross from the junction of Watling Street and Market Place, around which the market would have been centred, and moved it to his estate at Swithland where is still stands. He replaced this with a purpose built stone pergola in the same location which remains to this day. The market continued to be held on this location with it’s heyday in the 19th century with the locally produced “Mountsorrel gloves” much in demand,

A replica of the original Butter Cross was commisioned as part of the Parish Centenary celebrations in 1994 and completed by local artist Michael Grevatte (who lived at some point on Watling Street); it now stands proudly outside the Peace Gardens at the junction of Sileby Road and Loughborough Road close to the town centre. Moving the original Butter Cross back to the town was looked at, but sadly the monument is now far too fragile to withstand another move.

Although the original fair was discontinued in 1873, the town continued to hold sporting events and parades bringing together the surrounding communities until the early 20th century. This tradition has been rekindled in recent years with the “Mountsorrel Revival” being held on the 2nd Sunday of each August since 2016 and has continued to grow year on year ever since!

TRANSPORT

Being located on the main route north/south along the Soar Valley, Mountsorrel has always been linked to transport passing through the area, be that in defence and control by the castle or as a natural route for the later main road (or turnpike as it was know in earlier times), the canal and the railway.

The Turnpike

Since Medieval times there has always been a road running north-south along the raised western bank of the River Soar valley; historically there have been only limited places where crossing of the river is possible, and Mountsorrel sits on one of them. Before the river was canalised for easier transport the land to the north of the town towards Loughborough was likely marshy due to the low lying flood plain, a road from the east (the old Slash Lane) passed over this bridge/ford up the embankment beyond to the main road.

A turnpike road was in essence a toll road where the tolls changed would be used to maintain that section of road. The UK’s first ever turnpike was built between London and western Scotland in 1726, and in our area this ran through Market Harborough, Leicester and then onto Loughborough (this was MUCH later renamed the A6). The toll station to the south was in Leicester on Belgrave Road near the market, and the one to the north was in Quorn, situated approximately where the mini roundabout next to the White Horse pub is (later moved to the junction of Woodthorpe Lane in Loughborough). To support the travellers and cash in on this route many coaching inns were built along the road and two can still be seen in the town, The Swan Inn (formerly the Nags head) and what was The Grapes hotel (now 2 houses); both of these still show the old coach entry archways.

The Canal

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, a means of transporting coal, iron ore and other valuable heavy bulk goods between the factories, mines, kilns and forges was needed, as well as a means of delivery the final products to the rapidly growing cities and their growing demand.

As the road network of the time was unsuitable for heavy wheeled transport (especially fragile goods), a vast network of canals was built. The River Soar was made navigable as far as Loughborough as a branch of the Grand Union Canal in 1780 and was extended through Mountsorrel to Leicester by 1794. Originally the medieval stone 4-arched bridge was retained as part of the redesign but this was blown up and replaced by a metal one in 1852 when it became unsuitable for the increased heavy goods traffic if was being subjected to.

Initially to goal of the canal was to facilitate the moving of Derbyshire coal into Leicester (which it it did to such an extent that it soon became uneconomic to mine coal locally in significant amounts even for local use). Locally quarried granite was soon brought down to the canal by horse drawn cart where it was loaded into the canal’s narrowboats to take advantage of this new revenue stream. It is notable that quarry activity also dramatically increased at this time to meet the new demand that the canal traffic was generating, lime from Barrow also took advantage of this. As the main quarry at the time was Broad Hill, the route would have taken the carts down Watling Street, through Market Place to the canal’s dock on Main Street (now named Loughborough Road).

The Waterside pub sits alongside the canal’s lock gates, this was called the Duke of York since its building in 1795 until Everards Brewery changed it in 1965. According to an advert for the pub when it was sold in 1869 it had “stabling for 12 horses, piggeries, with numerous offices, with garden and orchard”.

A loaded narrowboat would take 2-3 days to get to London with a full load of granite assuming it could travel through the night, or more likely up to a week if restricted to daylight travel only, this was a huge improvement over the nightmare of trying to get loaded heavy wagons over the rough mostly unpaved roads of the time. The glory days of the canals was not to last long though!

The Railways

The Soar valley didn’t only provide a logical route for roads and canal transport but also from the mid-1800s, the new steam powered railways too. In 1839, the Midland Counties Railway (MCR) drove their line southwards through the valley from Derby and Nottingham down through Loughborough, Barrow, Sileby and Leicester and then onwards to Rugby; this was opened in our area on May 4th 1840. The financially struggling new company merged with 2 other local railway companies in 1844 to form the Midland Railway (MR). Our local section of line has been in constant operation since as part of the Midland Mainline.

(North in downwards on this map…)

These early railways’ main income was always going to be from the transport of freight rather than passenger traffic, and in 1858 an act of Parliament was passed allowing the creation of the “Mountsorrel Railway” which would link this main line to the Mountsorrel granite quarry. As part of this spur an 80yard long brick viaduct was built over the river over which the rail line ran. This is still in existence today and still bears the date 1860 in which it was completed. The bridge continued to carry quarried granite by rail to the Sileby sidings until the 1977 when the track was removed and replaced by a conveyor belt. This belt is still in use today.

The Midland Railways didn’t continue to monopolise the granite from Mountsorrel for long; in 1898 the Great Central Railway (GCR) drove their own line northward from Leicester through Quorn and created their own spur to the quarry from their Swithland sidings to the quarry. This was closed in 1964 but has now reopened as part of the preserved Mountsorrel Railway.

Despite being sandwiched between the Great Central and Midland Railways, Mountsorrel has never had its own station. The nearest stations were “Barrow upon Soar and Quorn” on the MR and “Quorn and Woodhouse” on the GCR. At one point in the late 1830s an act of parliament was passed that would have allowed the MCR to build a rail spur from near Barrow to opposite the Duke of York pub and the canal – primarily to transport quarried granite by horse drawn trucks; after the amalgamation of the MCR into the MR in 1844, this plan was ultimately shelved in favour of the later 1858 plan.

It’s interesting to see though in the Parliamentary gazetteer of 1845/6 Mountsorrel is described as “7 miles north of Leicester, and 105 North by west of London, a little to the west of the Midland Counties railway, with which it communicates by a branch line.” As far as we known – this was never built!!

A6 Bypass

The final part of transport in the town is the A6 (previously the old turnpike road); until October 1991 the main road through the centre of town was also the main road from Leicester to Loughborough, and also carried all of the quarry’s heavy lorry traffic! Debated in Parliament since at least 1978 but the object of local campaigns for at least 50 years, the Mountsorrel and Quorn bypass construction was given the go ahead on 18th August 1989. Opening 2 years later it immediately slashed the amount of traffic transiting through the town and took the quarry traffic directly only the A6 bypass via the newly constructed Granite Way.

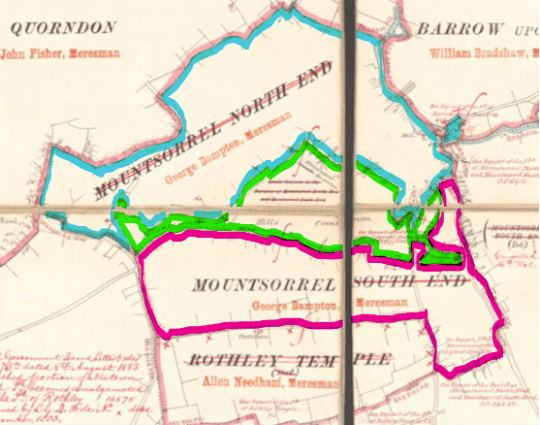

NORTH/SOUTH SUPERIOR/INFERIOR AND THE COMMON

In 1080, which was approximately when the castle was built, the area was already split between 2 parishes, Barrow to the north (Earl of Chester) and Rothley to the south (Earl of Leicester). As Mountsorrel castle lay pretty much on the border, 2 new areas were set up, Mountsorrel North and South; these were each carved out of the previous parishes but ownership was retained by their previous Lords. These were originally known as Mountsorrel Superior (south) and Mountsorrel Inferior (north) – but not in the modern meaning of the words.

Under the Mountsorrel Enclosure Act of 1782, a pre-existing section of common land situated between the two parishes (the green area on the map above) was confirmed as for common usage; this was a formalisation of an historic area that had already been long in common use, much of the large area in the centre of it though has now been quarried away. The remainder however, forms the heart of Mountsorrel Conservation area that was set up in 1977 along with an area that approximates the town boundary at the end of the 19th century. This Conservation Area sadly arrived too late for many fine but weary buildings in the town centre that were torn down and redeveloped in the 1960s.